For your reading pleasure, please enjoy our Oscar Lessons interview with co-writer Patrick McHale about scripting Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio from Backstory Magazine’s issue 49 – now available to read! If you enjoy what you’ve read, we hope you’ll join us to read the rest of the issue by subscribing to Backstory Magazine!

Patrick McHale on writing Netflix’s stop-motion success story and the many changes made in the adaptation

By Danny Munso

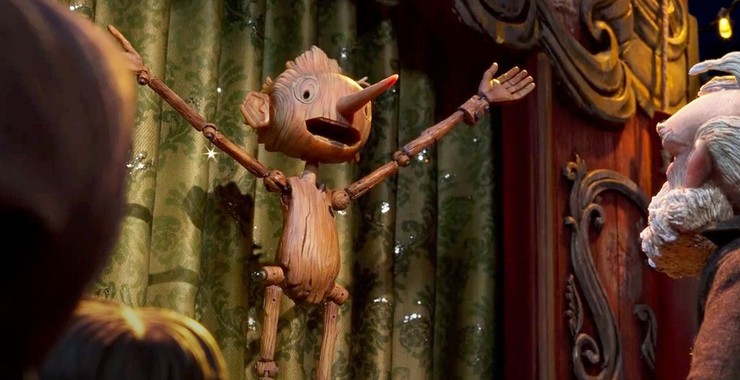

Guillermo del Toro has often said that a stop-motion animation version of Pinocchio was his passion project, and the film’s lengthy development timeline would certainly seem to confirm that assertion. The director first announced plans for the project back in 2008, planning to use illustrator Gris Grimly’s 2002 drawings from a new version of Carlo Collodi’s classic 1883 book The Adventures of Pinocchio as inspiration. In 2011, del Toro and frequent co-writer Matthew Robbins completed a script with their unique take, which would be co-directed by Grimly and longtime animator Mark Gustafson. As happens in Hollywood, financing fell apart and the project was put on hold for years. Del Toro revived it in 2017, with the intention of directing the film himself alongside Gustafson and with the involvement of Netflix. But rather than use the previous screenplay, he wanted a fresher version: Enter Patrick McHale.

McHale had previously been a writer and creative director for the acclaimed Cartoon Network series Adventure Time and was coming off his creation of that network’s Emmy-winning miniseries Over the Garden Wall when he agreed to sign on. It would be natural instinct for McHale to read the version Robbins co-wrote, but del Toro had other ideas. “He didn’t want me to read it,” McHale says. “He wanted to see what my take would be on things. There may or may not be elements in ours that carried over, but I don’t know because I still haven’t read that version.” Instead, del Toro and McHale sat down for several conversations about del Toro’s hopes for the film, which would take major elements from Collodi’s text while incorporating the director’s own ideas. “He had been thinking about it for all those years so he had a rough outline in his head of what he wanted to do. We talked about his vision for it and started going back and forth with pages.”

Initially, del Toro and McHale each took 20 pages to write on their own before they would hand those over to the other. Eventually, though, a first draft was needed for production, and that plan went out the window and they each quickly reworked the other’s scenes. Del Toro, as the director and creative force behind the project, obviously had final say on what went in, but he encouraged McHale to hold firm on an idea if need be. “If he changed something I wanted to change back, he wanted me to fight for it,” McHale says. “That happened on quite a few things, and I think we found a balance where we both ended up happy.” Their co-writing extended to some of the film’s musical numbers, which del Toro intended to pen with the movie’s composer, Alexandre Desplat (Oscar winner for del Toro’s The Shape of Water, among other wins and nominations). But after leaving a rough draft of the lyrics in some of his pages, McHale—who writes and releases music of his own—began rewriting. Del Toro loved his changes, and McHale eventually became co-writer on several of the film’s tracks. One element McHale leaned on in the early days was the large amount of character designs already completed for the film by del Toro’s longtime concept artist Guy Davis, also the movie’s co-production designer. “(The drawings) definitely helped inform the tone,” McHale says. “Specifically with Pinocchio—with the fact that he was so roughly hewn, we wanted to showcase that in the writing and meld all those elements together. In some of my first meetings with Guillermo, Guy was there as well and we would talk about design in the same breath as story. It was all kind of intertwined.”

Set in 1940s Italy, Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio is the story of the title character (voiced by Gregory Mann), a wooden puppet created in a drunken rage by a grieving Geppetto (David Bradley), whose son Carlo (Mann) was killed in a bombing raid gone wrong. After the Wood Sprite (Tilda Swinton) gives Pinocchio life and a conscience in the form of Sebastian J. Cricket (Ewan McGregor), Pinocchio strives to be the son he thinks Geppetto deserves. However, he soon falls under the influence of Count Volpe (Christoph Waltz) and his monkey assistant, Spazzatura (Cate Blanchett—yep, really), who promise to make him a star. Pinocchio eventually sees through Volpe and escapes, before landing in a boot camp where young boys are trained to fight in the war. After the camp is attacked by Allied forces, Pinocchio is captured by Volpe, who threatens to burn him for leaving. Spazzatura saves Pinocchio, but the pair end up inside the belly of a giant dogfish, where they are reunited with Geppetto and Cricket before all escaping.

While the main beats of the classic Pinocchio story are clearly there, the details are often different in del Toro and McHale’s version. But del Toro really wanted to hone in on one aspect of the story that was always in the subtext of Pinocchio: the fact that Geppetto is replacing one son with another and the “replacement” child’s desire for his father’s approval. In most versions of Pinocchio, this takes the form of the puppet desiring above all else to become a real boy. That is never on the table here. Pinocchio’s driving goal at the end of the film is to be accepted and loved by his father the same way Carlo was. That complex relationship between Pinocchio and Geppetto is the emotional spine that makes this take on the story stand out. “I think any parent, when you have a child, you have these expectations of what they’re going to be like,” McHale says. “Then you see them not being that way pretty quickly, and it’s like, Did I do something wrong?You start second-guessing how you are as a parent and how they are as a child. All those things are natural. All of that was there thematically, and it’s always sort of been there in the book. For Pinocchio, it’s not as much about being a real boy as much as it’s about how he really loves his father and feels he keeps messing it up.”

Volpe and Spazzatura are plays on the characters of the fox and the cat, important figures in Collodi’s version and made famous in Disney’s beloved 1940s adaptation. But in Collodi’s story—and the Disney version—the fox and the cat are merely con-artist conduits before Pinocchio meets another villain in the story, Mangiafuoco (Stromboli in the Disney film.) In del Toro and McHale’s first draft, Mangiafuoco—which is Italian for “fire eater”—is indeed the main antagonist, but something didn’t track. And so del Toro threw an idea out there: Why not make Volpe the main villain and cut Mangiafuoco from the story altogether? “It just kept not feeling right,” McHale says of the original plan. “Volpe kept being a more compelling character to write. At some point Guillermo asked if we should get rid of everybody else and just keep him. He liked the design and he liked the way we were writing him, so it just made sense at a certain point.” The removal of Mangiafuoco opened up the story in a major way and removed some of the clutter that came from the plot machinations of moving Pinocchio from one antagonist to another. “There were just too many characters. And we had already made so many changes from the book at that point, so it didn’t seem like we had to stay close to that in any way.”

There was an unintended consequence of this major change, though. A Mangiafuoco puppet had already been created so it could be animated once filming began—a massive, beautiful creation that was now going to waste. And yet it does live on in the film, just not in the spotlight it once had reserved: In the scene where Pinocchio visits Volpe’s circus, the Mangiafuoco puppet appears as the strongman in a couple of shots. The writers also struggled in early drafts to find the voice of Cricket. They grew so frustrated they had a serious conversation about removing the iconic character altogether. Out of desperation, they tried him as the story’s narrator, and something seemed to click. In the film, the narration is explained that Cricket is writing his memoir, and the character was injected with a new life…and arrogance. “We finally hit on a better way to write him and make him self-obsessed a little bit,” McHale says. “That led to him learning to not be so self-obsessed later in the movie. It started writing itself. Then when Ewan came in and read all those lines, it was so funny. We knew we had found it.”

From the start, del Toro was adamant that this story needed to be set during World War II at the height of fascism in Italy. The director is known for commenting on fascism in a lot of his past works in both subtle and overt ways, and he wanted this film to do the same. For his part, McHale was unsure about wading into those heady waters. “That’s something I’m not as comfortable with in my personal work but something he has obviously done in his,” he says. “That was definitely a new element for me. It was a little daunting. It’s an animated film, but I didn’t want to be false with it. I did a lot of research and reading. I tried my best to be as truthful as possible not only with facts and locations but also emotionally truthful.” Del Toro upped the historical ante with the inclusion of Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. In the movie, Mussolini turns up at Volpe’s show, where Pinocchio embarrasses the dictator and Volpe. Mussolini’s presence in the story made McHale uncomfortable—until he saw the exaggerated design del Toro had planned for the character. “You don’t want him to come off as a cool character. Visually, he has a striking pose in some photographs, so if we only have one or two shots of him in the film, you don’t want the takeaway to be that he was cool. His behavior is very weak and insecure throughout history, so it was good they found a way to show that visually rather than have us try to figure out how to communicate it in one line of dialogue.”

The compromise was an apt snapshot of how del Toro and McHale paired to craft one of the year’s most successful films. It has become an awards-season favorite, nabbing up Best Animated Feature trophies from the BAFTAs, Golden Globes, Annies, Producers Guild and multiple critics groups. To say it is the frontrunner to earn del Toro his third Oscar is an understatement. “Guillermo and I both have similar outlooks on life in some ways and very similar senses of humor,” McHale says. “I think we both gravitate toward similar comedy and similar drama and similar horror in art and film and literature. This movie has a lot of different elements of all those things. It was a nice meld for both of us.”

If you’d like to subscribe – feel free to use coupon code: SAVE5 to take $5 off your subscription and get instant access!

All you need to do is click here to subscribe!

There’s plenty more to explore in Backstory Magazine issue 49 you can see our table of contents right here.

Thanks as always for spreading the word and your support!